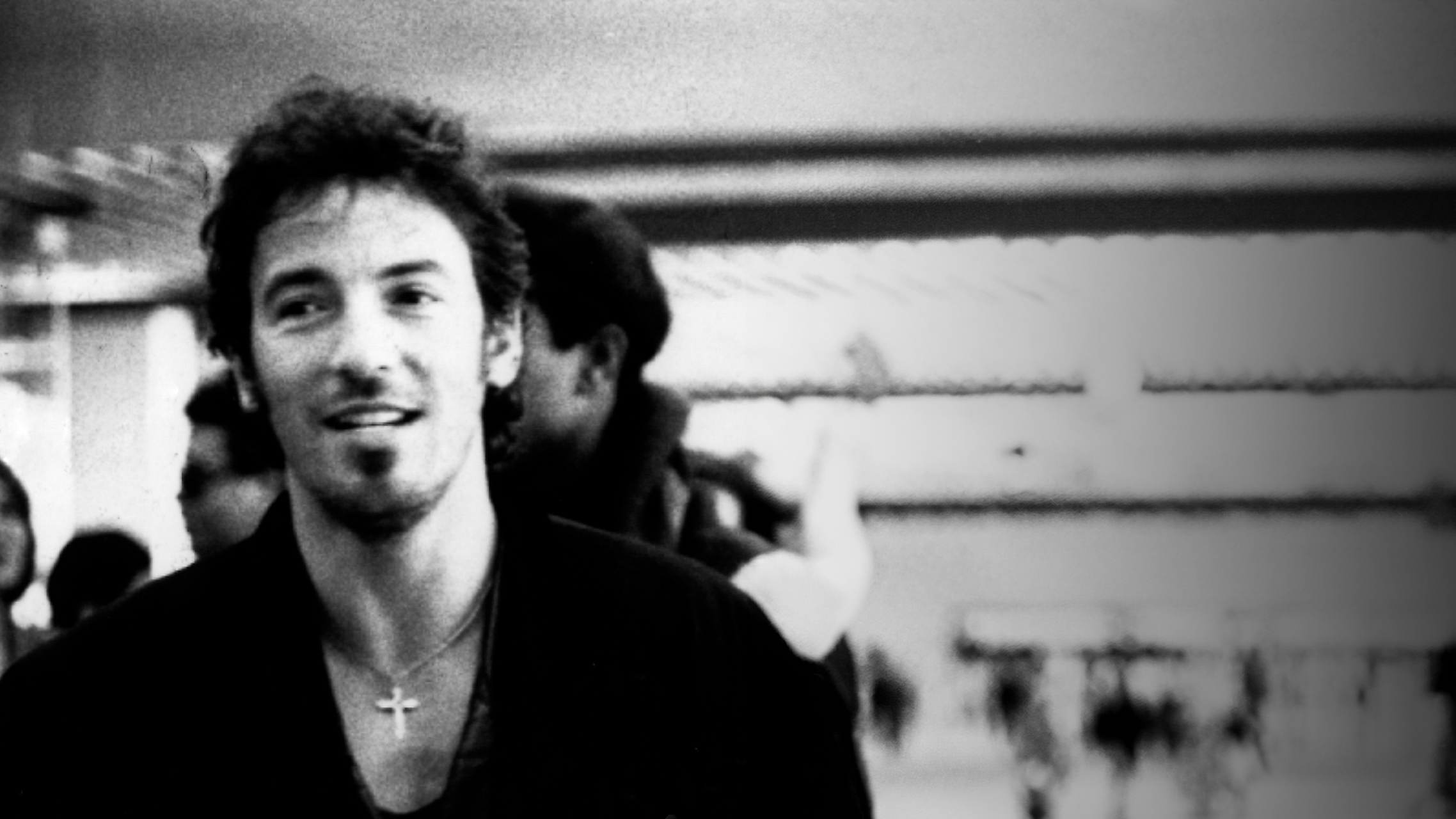

I recently attended a Bruce Springsteen concert in Syracuse, New York. Waiting in line for entry into the standing-room-only pit area, I noticed one fellow concertgoer approach another. Apparently strangers, they shared the same T-shirt—bright red, emboldened with the words: “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City.” The words refer to the title of the closing track from Springsteen’s 1973 debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park. With no particular reference to that song title, the initiator of the exchange informed the other that they were both about to partake in the religious experience that is rock and roll. It sounded like something he had read somewhere, but it nonetheless reflects the place that rock music holds in the lives of many of a certain generation, the Baby Boomers. Later, during the concert, Springsteen launched into a standard feature of his live shows, exhorting the crowd to reverie in the tones of a Baptist preacher; in response, a middle-aged man standing next to me shouted “Testify!” As if the music from a three-hour long show were not enough, my mind was swirling from all this religion talk.

Bruce Springsteen was raised Catholic. He is no longer a practicing Catholic. Is his music Catholic?

I often cringe when Catholic cultural commentators try to attribute a Catholic quality to the works of artists simply due to some tenuous connection to Catholicism. When Jimmy Buffett died last year, I was surprised to learn that he had been raised Catholic; I was utterly unconvinced by some efforts to read Catholic themes into his work. He was a good singer-songwriter, and sometimes that’s enough. Springsteen’s Catholicism demands more serious consideration, especially after the publication of his memoir, Born to Run (2016), and his subsequent Tony Award–winning one-man show, Springsteen on Broadway (2017). Earlier biographies had acknowledged Springsteen’s Catholic upbringing and his mother’s Italian ethnicity, but quickly moved on to chronicle his road to rock star fame. Springsteen’s own late-career writing and performance made clear the deeply formative nature of the Church in his childhood and the other ethnic dimension of his family life: despite the Dutch roots of the Springsteen name, the paternal side of his family was Irish.

Springsteen celebrated his New Jersey roots at a time and in a business where being from New Jersey was about as unhip as any aspiring rock star could get.

Early in his career, Springsteen’s handlers tried to market him as the “New Dylan” and were disappointed to learn that he was not Jewish, despite his Jewish-sounding last name. The ethnic revival of the seventies witnessed the popularity of the Italian Catholic-themed films of Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, yet Columbia Records showed no interest in playing up Springsteen’s ethnic Catholic roots; Springsteen himself made no particular effort to highlight those roots either. The saint of “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” owes far more to the American pop culture ideal of an urban hipster than to anything distinctly Catholic:

I had skin like leather and the diamond hard look of a cobra

I was born blue and weathered but I burst just like a supernova

I could walk like Brando right into the sun, then dance just like a Casanova.

Still, for those with eyes to read and ears to hear, there was a Catholic cultural trace in the very title of the album, which identified Springsteen as someone from somewhere: Asbury Park. Unlike Dylan, the self-styled drifter always reinventing his persona, Springsteen celebrated his New Jersey roots at a time and in a business where being from New Jersey was about as unhip as any aspiring rock star could get. Always in the shadow of New York City cool, New Jersey suffered the additional stigma of post-industrial urban decline: Asbury Park, and even more so Springsteen’s hometown of Freehold, were places no one would want to go and most would like to escape. Springsteen made his first commercial breakthrough celebrating escape in Born to Run (1975), but he never left his provincial, parochial roots behind to reinvent himself in the classic American style. Culturally, at least in part, he stayed local. This, I would argue, situates him in the Catholic cultural landscape of his time.

Localism is, of course, not an ideal unique to Catholic culture. It is, however, an ethos distinct to urban Catholics in postwar America. In the 1950s, all of America was born to run, fleeing from the cities to the suburbs. As historians such as John McGreevy and Gerald Gamm have observed, attachment to geographic parishes made Catholics far more likely than Protestants and Jews to remain in the city, even when this brought confrontation with the new population of African Americans migrating to Northern cities in search of jobs. Since the age of mass immigration, the American city had taken on a Catholic character and was understood, usually in a negative way, as a Catholic place. When the New York City, Tammany Hall politician Al Smith ran for president in 1928, he was attacked by mainstream Protestant America for being Irish, Catholic, and urban. John F. Kennedy put the ghost of Smith to rest in 1960 and achieved his razor-thin victory in part by presenting a polished, suburban image indistinguishable from White Anglo-Saxon Protestant America. Urban Catholics celebrated him as a hero even as they continued to cling to older cultural ideals rooted in urban Catholic life. The ethnic revival of the 1970s generally identified ethnics as urban dwellers struggling against the new threats of de-industrialization and redevelopment.

Localism can be a tough sell to a national audience. Jersey pride notwithstanding, Springsteen wanted to be a famous rock star and sell as many records as he could. He seemed to get his wish in 1975 when the release of Born to Run earned him the cover of both Time and Newsweek in the same week. With the title track seeming to celebrate the classic American themes of freedom and escape, the album sold 700,000 copies in the first year alone. Still, Springsteen would not see any similar commercial success until 1984’s Born in the U.S.A. Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978) was, compared to its predecessor, a commercial flop. Through the rest of the seventies, Springsteen had trouble appealing to audiences west of Cleveland. In a bootleg recording from a concert in San Francisco on the Darkness tour, Springsteen introduces the song “Racing in the Street” by trying to describe the place in New Jersey that inspired him to write the song. At one point, someone from the audience interrupts with an inaudible comment, to which Springsteen responds: “You couldn’t have ever been there.”

The urban homelands of Catholic America are nearly as unknown and unknowable to most American Catholics as Springsteen’s New Jersey was to his San Francisco audience. Springsteen’s music is one way to get to know them. His classic late-seventies albums (Born to Run, Darkness, and The River) follow a narrative arch in which the protagonist first wants to run, then finds he can’t run, and finally discovers that he shouldn’t run. In the closing track of The River (1980), the narrator leaves behind the “wreck on the highway” and comes home to “watch my baby as she sleeps . . . climb in bed . . . hold her tight.” Simple lyrics but with a timely message. American Catholics have long acquiesced in the rootless mobility of modern American life and tried to forge a faith and spirituality appropriate to the highway that is America. Too often, this means finding the right books or cultural products appropriate to life on the road (or on the run). Books are fine, but as a basis for a culture, they are no substitute for place.

Emily Stimpson captures this contrast in her classic essay “Requiem for a Parish.” Writing about St. Stanislaus Parish in Steubenville, Ohio, Stimpson observed the cultural disconnect between the earnest and intentional orthodoxy of the students of Steubenville’s Franciscan University and the traditional, unself-conscious faith of the aging Polish parishioners of St. Stan’s. Stimpson gives due credit to the virtues and limitations of both forms of Catholicism but clearly wrote to raise awareness of the older ethnic model that was nearing extinction. Though Stimpson wrote her essay almost twenty years ago, little has changed with respect to awareness of that older way of life among the younger generation of earnest and intentional Catholics.

Bruce Springsteen’s music up to The River is one possible entry point for those interested in this world. Springsteen may not have retained the faith of the old Poles at St. Stanislaus, but he certainly knows their world. When he performed at the Tony Awards in 2018, he introduced the song “My Hometown” with the following childhood memories:

I grew up on Randolph Street with my sister Virginia (she was a year younger than me), my parents Adele and Douglas, my grandparents Fred and Alice, and my dog Sal. We lived spitting distance from the Catholic church, the priest’s rectory, the nun’s convent, the St. Rose of Lima grammar school. All of it just a football’s toss away, across a field of wild grass. I literally grew up surrounded by God. Surrounded by God and all my relatives.

We had cousins, aunts, uncles, grandmas, grandpas, great-grandmas, great-grandpas, all of us were jammed into five little houses on two adjoining streets. When the church bells rang, the whole clan would hustle up the street to stand witness to every wedding and every funeral that arrived like a state occasion in our neighborhood.

When I first started listening to Springsteen, I was unaware of the depth of his Catholic roots. Growing up in an urban Catholic parish in the shadow of the sprawling industrial complex of Kodak Park, I suppose I projected my experience onto his songs. Only decades later would I learn that the projection was not such an interpretive leap after all. In this sense, I suppose the Springsteen concert I attended was a religious experience of sorts.

Bruce Springsteen is part of Catholic culture and the American Catholic story. Culture is first of all accidental, only secondarily intentional. By itself, the accidental becomes tribal; by itself, the intentional becomes ideological. Springsteen ultimately left his accidental Catholicism behind and embraced an intentional American populism best captured in his biggest-selling album, Born in the U.S.A. I share some of that populist sentiment, but I generally filter his music through the accidental Catholicism present in his early work. Culture, like family, is messy. It includes all types of people, including those with whom we might otherwise never intentionally choose to associate—even formerly Catholic rock stars who do not seem particularly interested in creating a Catholic culture capable of restoring all things in Christ.

It’s hard to be a saint in the city.

It’s impossible to be a saint without the city.